“Do you know that a man is not dead while his name is still spoken?

”

THE PRECISION MEDICINE INITIATIVE defines precision medicine as “an emerging approach for disease treatment and prevention that takes into account individual variability in genes, environment, and lifestyle for each person.”

One of the biggest opportunities for artificial intelligence is its potential to power precision medicine systems and to pioneer a future in which every patient is treated as a true individual. We’re already on our way thanks to private companies like 23AndMe and huge scientific efforts like the Human Genome Project.

A great example of precision medicine in action comes to us via the Clinic for Special Children in Strasburg, Pennsylvania. At the CSC, the clinic routinely examines its patients’ DNA and uses genetic testing to offer more personalized care with tangible results. According to Delaware Online, this extends “to the point that a child doesn’t suffer from a brain injury or have to depend on a wheelchair.”

“Decades ago,” reporters explain, “it would take 10 years to sequence a human genome. Now, it takes 24 hours. The difference in treatment and outcome can be startling. Instead of picking treatments based on the average responses of a large population, doctors can look at one person’s genes and decide whether a specific medicine or treatment will be best.”

“In the not so distant future,” says Dr. Kevin Strauss, medical director at the Clinic for Special Children, “we will look at the genetic code of any individual as a vital tool or beacon that allows us to more intelligently, more rationally and more safely guide every aspect of their care throughout the arc of their lifetime.”

Predictive medicine has been useful when treating the local Amish population, as they typically intermarry and have genetic differences to the rest of the population that make them more susceptible to certain diseases. Another example is a disorder called ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency which can cause severe brain damage if left unchecked. Thanks to genetic testing, physicians can tell whether babies are susceptible and then make recommendations for dietary restrictions and medications that could help to stop the deficiency from progressing. Without this testing, physicians would have to wait until the child fell into a coma before they were able to provide a diagnosis.

“The clinic has also been able to reduce a condition called Maple Syrup Urine disease in the Lancaster community by 95%,” the report concludes. “The condition, which is known for making an infant’s urine smell like maple syrup, can consist of serious symptoms like seizures. If untreated, it can lead to death. A common form of treatment is avoiding foods with a high amount of protein. By catching it in newborns before symptoms appear, the Amish Lancaster community saves about $8 million every year in hospital costs.”

The Risks of Robotics

Robots are all well and good, but only when they work as they’re supposed to. One interesting case was brought to my attention by NBC News after a series in which over 250 reporters in 36 countries investigated medical device alerts from across the globe. Here, Cynthia McFadden and Kevin Monahan report from Iowa while Emily Siegel, Andrew W. Lehren and Pauliina Siniauer report from New York City.[1]

Our story begins in Iowa, where Laurie Featherstone is about to have a hysterectomy. Just before the surgery was due to take place, she was asked a question she wasn’t expecting: Would you like the surgeon to use a robot to carry out the procedure?

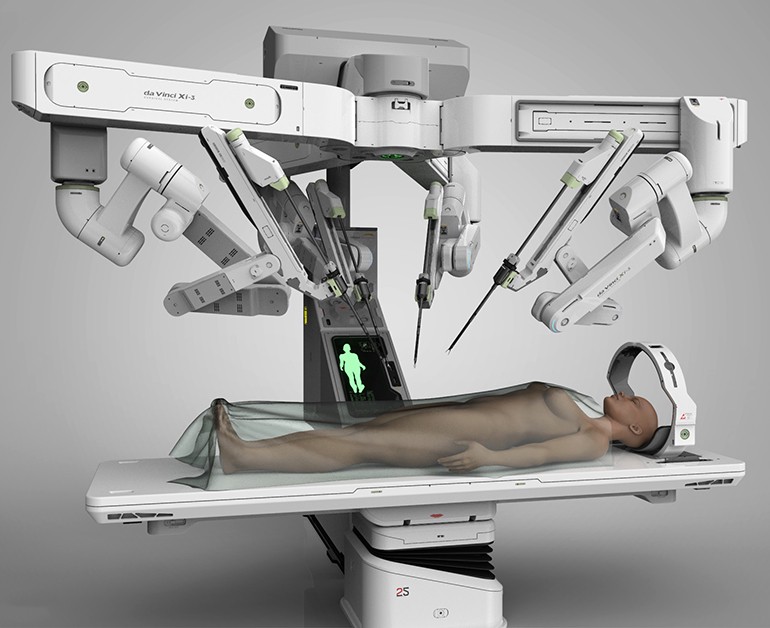

The robot in question was the da Vinci surgical system from Intuitive Surgical, and the doctor herself recommended it because it had less downtime, less scarring and a complication rate of below 3%. It was also said to reduce recovery time, and so Featherstone opted for the robot. Everything seemed to be going well…until a couple of weeks later, when complications started to make themselves apparent.

“Excess fluids accumulated in her kidneys,” the authors explain. “An ailment called hydronephrosis. There was an injury to one of her ureters, the duct that carries urine from the kidney to the bladder. One of her doctors wrote in her medical records that he assumed ‘the problem is a thermal injury’ and was ‘due to robotic hysterectomy’. Her ureter was burned and her colon damaged during the surgery, according to her medical records. Her prognosis calls for a permanent colostomy.”

Featherstone initially filed a lawsuit against both Intuitive and her doctor’s practice, but she later withdrew it after coming up against the statute of limitations. Still, it goes to show that robotic technologies come with risks as well as advantages. That’s what makes them such an ethical minefield.

Dr. Robert Poston, chief of cardiothoracic surgery at SUNY Downstate Medical Center, is a keen user of the device, but he does also warn that some surgeons start using it with insufficient training. “It’s woefully inadequate, the way it’s currently being done,” Poston says. “We shouldn’t be operating until we’ve done all of the training that we think is reasonable. We should live in a world where we practice brutal transparency with our patients. So if we lived in that world, we would tell the patient, ‘I’d like to operate on you but I didn’t have the time or money to have all the training that I think I ought to have had. Is that okay?’”

The problem is that in too many cases, we focus only on the advantages of robotics without provisioning for what to do if they go wrong or cause unintended side effects. The FDA doesn’t have jurisdiction over many of these devices, which means that in many cases, it’s up to each medical facility to decide when staff is ready to use robotic devices.

Poston says, “The root cause is the training. The willingness to sell robots to people and promote them doing surgeries when they aren’t adequately trained, the willingness of hospital credentialing committees to sign off on them and allow them to do it.”